First of all, my mother is not going to be happy that I posted this. So…sorry, Mom.

Other than the much more redemptive Whose Mouse Are You?, Harold and the Purple Crayon is the book I remember her reading me most. I loved that book—I still do—and I too read it to my children.

I first read it to them when I wanted them to hear a story, something of an allegory, of the fall of mankind. And that is how I explained the plot.

I don’t know when I began to see Harold’s world the way I do now, but I don’t ever remember seeing it any other way. I remember feeling sorry for Harold when I was a little boy (I don’t know if my mother knew that). It always seemed to me to be a story about a lost little boy desperately trying to find home while ever running farther and father away. It always seemed to me a story about every man. That’s how I read it to my kids. My mom rebuked me for it. Then I wrote this (back in 2016). She hates it.

When I saw “they” made Harold the movie, I expected to be disappointed (especially after the ignominious Where the Wild Things Are 📽️ ). I suppose I can’t say conclusively I was disappointed, but I can say the two times I’ve tried to watch it I’ve fallen asleep (#typical—the second of which my whole family was mad at me because I insisted we watch a movie we’d all already seen together minus the one who slept through it).

So, consider this ^ a disclaimer. I think Harold’s world is a meant to place a mirror before us and so leave us with a warning of making our beds in a world of our own making.

With no further ado—

Originally Published Here, June 2016

Harold and the Purple Crayon is the saddest book ever written. It is either a book about a lost son or a book about every man, but if it’s the latter it tells the story in a way that reminds us that, in the end, we’re all lost in the same way looking for the same Home—and that finding it will require casting both crowns and crayons.

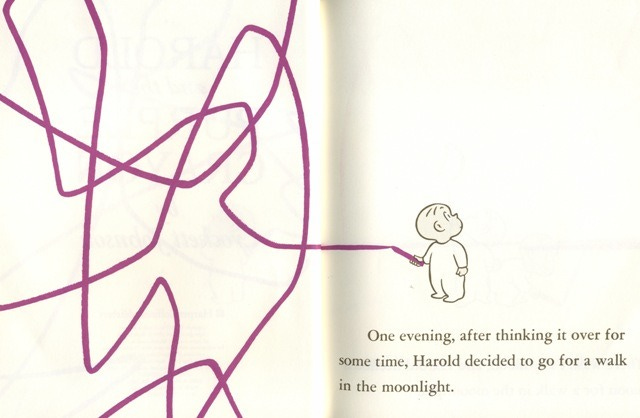

We enter the story and are introduced to Harold on the other side of some unnamed conflict. Order has given way to chaos. Something has gone terribly wrong.

But then: stillness, as if suddenly removed from a world outside his control, into quite something else. Harold looks away to the night, turning a blind eye to the domestic disturbance behind. He is free. He can now escape into the world of unfettered creativity. The night is filled with endless possibilities. Harold has a crayon.

So Harold leaves home to follow a moon of his own making, reflecting his own light in a world built around a moon. He descends on a two-dimensional plane in search for he knows not what. The world is a surface, a canvas for his self-expression.1 He has been crowned with a purple crayon as creator, author of life–all ultimately autobiographical–beginning by being scribbled out onto a blank canvas with no edges, no limits, the pure and unbounded freedom of the will.

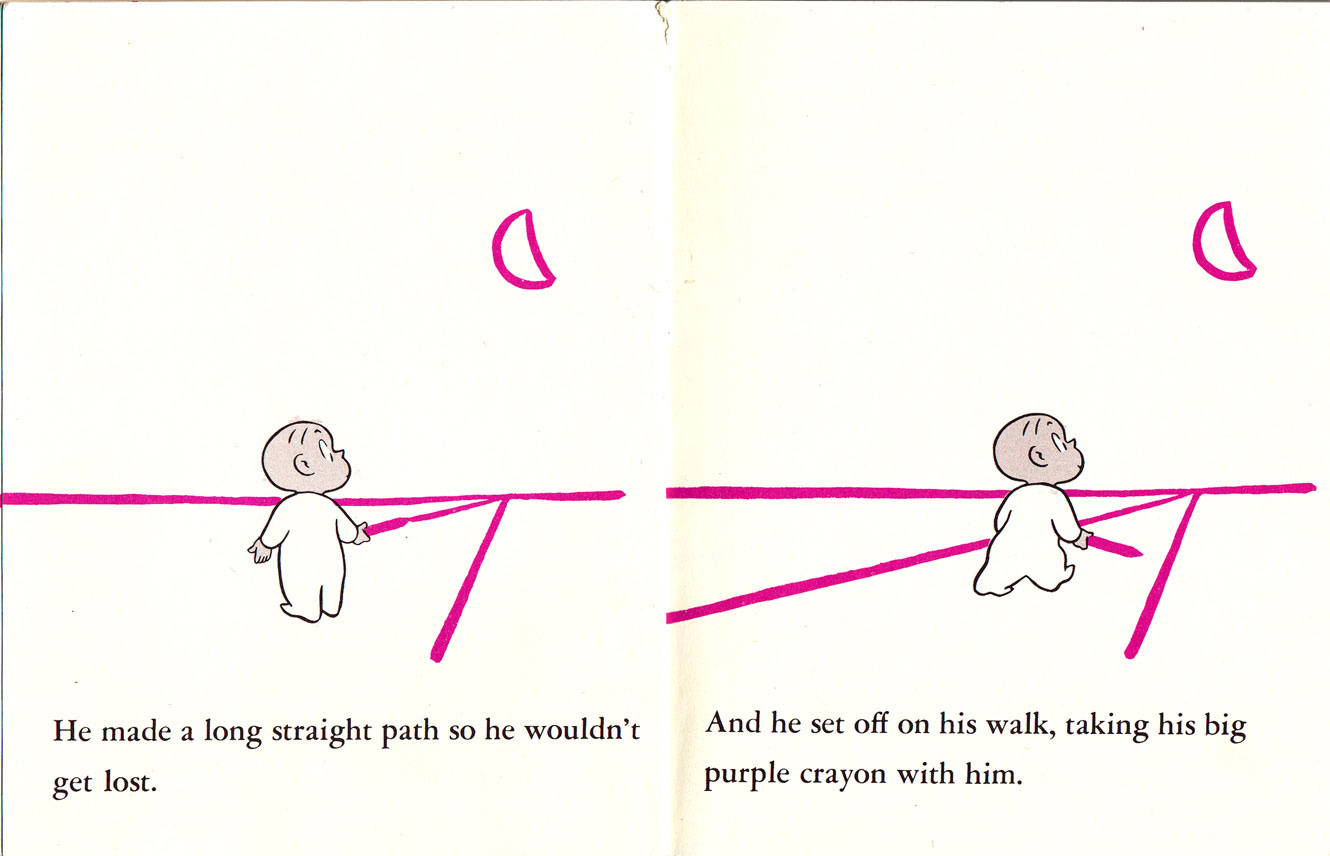

Thus, Harold begins by making a place to stand, the ground beneath his feet, and the light for his path. Naturally, it begins straight and narrow, but eventually, and just as naturally, he wanders off. Now the night is following him.

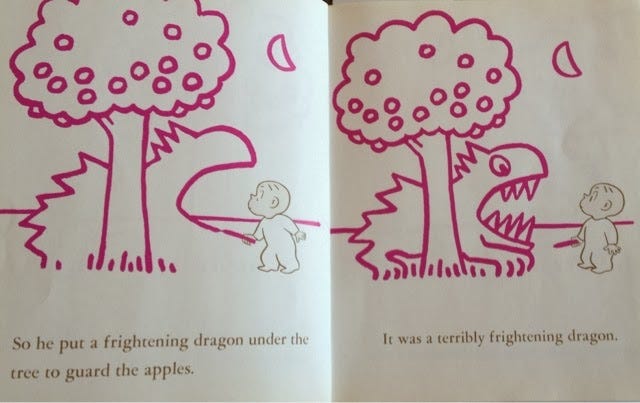

Eventually, he needs a companion–for it is not good for man to be alone–so begins expressing himself to find a suitable helpmate. But something foreign seems to be embedded in his memory, something that either looks nothing like him on the surface or quite like him beneath. We begin to see what has been lurking about in Harold’s heart. It is an image curiously familiar in Western culture, a half-evil fruit tree protected by a very real monster.

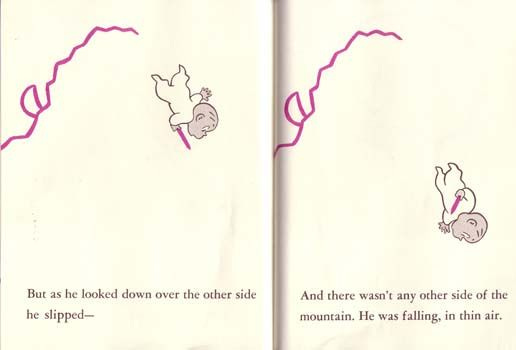

In a new form of self-expression, Harold creates a monster to guard a secret tree but discovers that the monster has a mind of its own and is no respecter of persons. The thing that was inside him now tried to eat him!

[Didn’t Adam name the serpent?]

Driven away in a panic by the creature of his own making, Harold accidentally draws a great deluge but thankfully saves himself on a boat. It is still night.

Harold makes it to land. He is famished. So he listens to the voice of his appetites to instruct him in his need for nourishment. Harold lives on pie alone.

Turns out he’s got god-sized eyes but only a human-sized stomach. He is left with a surplus of sweets. The producer creates consumers. From the surface of things, you’d never imagine this entire economy were born of a lost little boy’s aimless appetites. It all seems much happier than hunger. Everyone smiles at the pies—of course they smile—because in Harold’s world everyone is starving.

Harold feels sick. Maybe it was the pie, but it seems closer to the heart than the gut. He decides to start looking for home. He proceeds to draw a tower reaching the heavens. He now begins search for home. But his search never leads him to turn around, to go back, to regress and become like a child. His search leads him upward and onward. But a certain gravity eventually pulls him from the top of his tower back down to the surface. The height of his power turns out to reveal only how far he could fall.

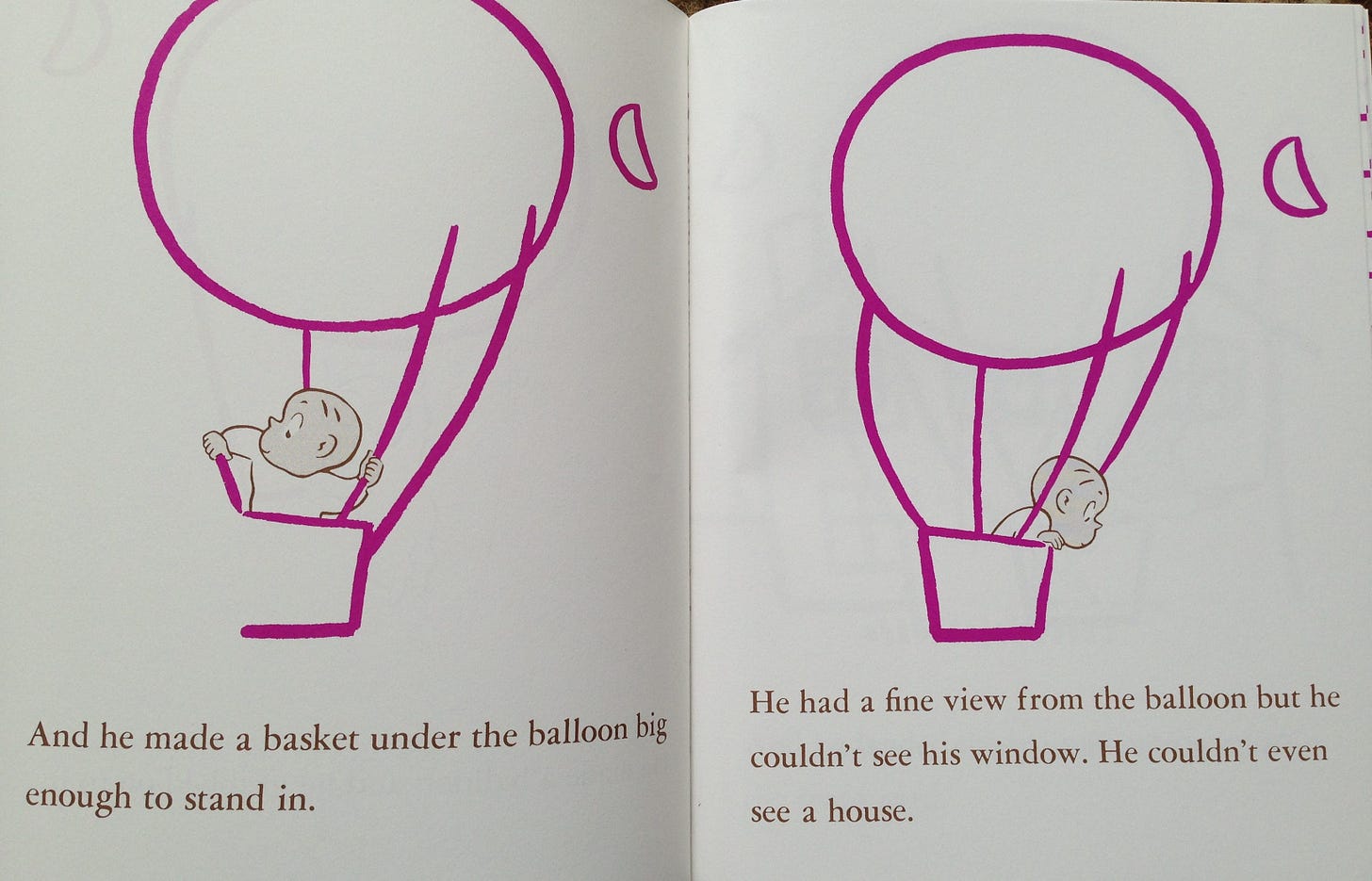

But he saves himself again by making a balloon. He has defied nature itself floating first and now hovering over otherwise abysmal conditions.

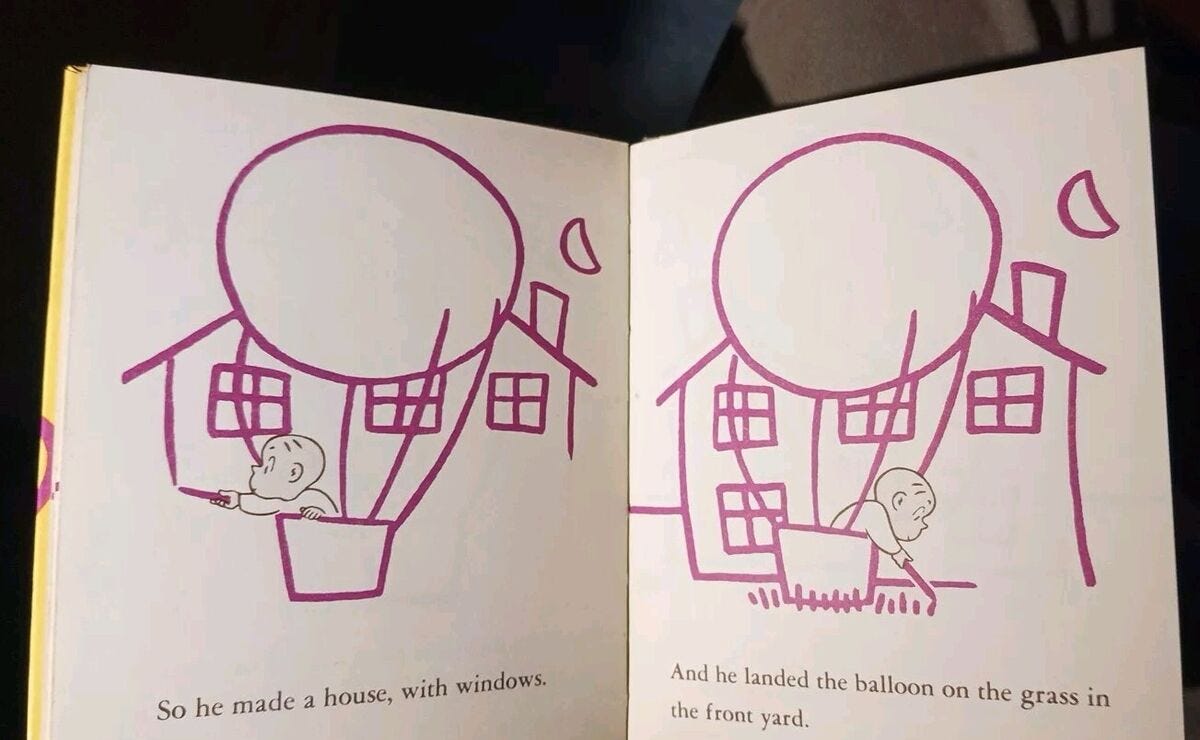

With no ground beneath him, however, floating seemed hardly any different from falling. This caused him to wonder about things like motion and the position of his moon, and for a moment the source of its light—never mind. He did not bother long with that thought and drew new ground to stand on. It then occurred to him rather than returning home he could just make the home he remembers. He draws it exactly how he remembered it—yet it was still utterly foreign to him.

But he puts his hand to the plow again, except not the plow at all. He is now into real estate, with city-building ambitions, like Cain and Nimrod and Romulus and the rest. He sets out to realize new horizons with raw materials of mud, metal, and a wild imagination of zigguratic proportions. This new creation had been liberated from the creations of the farm, rather from a life of fighting with thistles and praying for rain.

He has still not once considered turning around. He continues to follow the moon walking away from the Source of its light. Even if home were behind him, there’s no reason to believe he could go back. Time doesn’t work that way, nor the human heart. He can no longer believe that the home he remembers in that latent longing is one he actually belongs to—only God remembers Eden; all that’s left for us is the longing.

But Harold, like his father and father’s fathers, stretch it in the wrong direction. It is infinite progress, not ancient memory, that must satisfy his eternal longing. So the cure for his aching existence must come by way of forgetting, for while ancient memory always seems to haunt every present moment, it still feels somehow more distant than the ubiquitously advertised future that is forever at our fingertips.

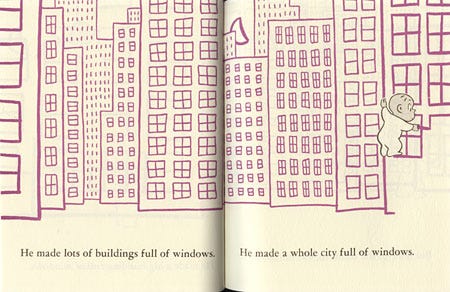

So Harold tries to give form to the haunted hole in his heart in order to create a home to belong to. He builds more windows, hoping against hope that he will discover through one the bedroom mirror hanging on the inside of his bedroom door at home. He builds an entire city. And in the saddest scene ever illustrated, an anxious little boy climbs his towers with crayon in hand making a kingdom of windows that only reveal the gaping hollow of his homesickness.

It’s as if all of human life were born out of some grand front porch that continually expands in the heart with age. And all we know to do is try to match its grandness with grandiosity. So white-knuckled men scrape the clouds in high flying home and high-rises that feel nothing like home. They feel like heartache, like homesickness, like arms of all humanity bursting out of the chest of the world, like Babel, reaching up for a home forever out of reach, like a title wave reaching up for the moon. It is the longing for the divine economy and the consolation of towers of human trade.2

Harold’s heartache creates an entire city the size of his homesickness. But it didn’t cure it. It is the saddest picture I have ever seen.

But Harold finds creates help—self-help. He has long become his own law-maker and judge, so now he creates law enforcement to do his bidding, what the Bible might call an ‘officer of iniquity’ (that peculiar sin not of doing evil but defining evil as good, the original sin and the meaning of that forbidden and ever ancient-present tree). Surely, he can trust law enforcement to help him find his way home. But, unsurprisingly, he is of no help. All he can do is enforce Harold’s laws, which only serves to reinforce Harold’s constitution of self-governance. Harold must stay the course. To turn back would indeed be unconstitutional.3

So he settles. He can neither find his home nor the light of day. He looks up to the lesser light of the night and wonders what makes it shine. He looks down again and sees his shadow, and continues to follow it.

Harold’s home will be framed around the endless night, his only vision of light, something like the vision in Plato’s cave—before the liberation. Refusing to turn around he will never discover the genesis of his sight, the very warmth that always seems to hit him from behind in the memory of a home he no longer can believe is real. So he exchanges the substance of an eternal past for the emptiness of a self-made future and builds his final home in the shadowlands of the night. He is now on the other side of that empty window in which the moon is forever imprisoned.

The story ends with the end of all possibility. Harold is not only given to the night, but any possibility of the morning with him. Harold will slip into oblivion, but only because he tried to create his way out of it. The only thing worse than embracing emptiness is denying it, which is the difference between the nihilism of creation and creation in nihilo, between hopelessness and false hope, between godlessness and the no-god, between an honest heralding of despair and today’s bullhorn gospel of progress: between the fall of Adam and the rise of Babel.

It is the far end of self-expression in the triumph of self-discovery, the absolutization of human freedom in rebellion to the Light. To reject our Source is to embrace the outer darkness. Harold has succeeded in constructing his hell.

Hell is the life that immortalizes emptiness as its god and when the paint dries will live forever in its image.

The book concludes thus:

“The End.”

Indeed.

O jealous moon

Don’t turn your back

That glory behind

Is a shadow of blackO jealous moon

Love the light as yourself

If seek your own glory

You’ll become something else

The enterprise of the no-god is avenged by its success.

—Karl Barth

Endnotes

Something like what, e.g., Robert Bellah and Carl Truman have called “expressive individualism” or “self-expressive individualism.”

If you’ve ever been a ‘passenger’ on the subway you’ve experienced the real lifeblood, the true spirit, of the city. Subways feel like a different realm—it is the realm where we bury our dead, after all—where the grandiosity of the city’s surface is deflated into a subterranean confessional. In a city’s subway the height of human reach above is curiously incommensurate with height of human beings below. Down there, we’re all small again, human again, where we’re all at the mercy of the same train, at the mercy of the same time, in a liminal existence where we’re all strangers just passing through. There is proximity, and there are infinite distances. The subway is an existential and allegorical reminder that soon our ride will be over, the train will move on, and we’ll be forgotten by those who never knew us. Is that what feels so human about the subway? Is that why it’s hard to ride the subway and not wanting to cry a little?

Human freedom conceived of as the freedom of choice itself, rather than the freedom to choose the Good, is what the biblical creation account refers to as the freedom to eat from the knowledge of good and evil. To affirm freedom as such is to commit the primal sin, because it is determining what is good without reference to God, the absolute Good whose ‘self-expression’ alone is “very good” (Gen. 1:31), and elevating the atomized human will, now untethered from God’s will, to ‘express itself’ in a groundless realm of nihilism, from nothing to nothing, and thus contrary of the realm of love, that is, reality / God’s eternally present act to create. In such an ‘outer darkness’ there are no stable self-transcendent coordinates that can be identified as ‘good’, and thus the exercise of the will itself becomes the absolute good, that is, the will to power (Nietzsche).

Harold had discovered this raw freedom on the first page, but he eventually builds an entire civilization on this foundation and organizes society based on its nucleus. Organizing a society around the sovereignty of the individual’s will-to-power, however, is at once basis of its eventual and seemingly inevitable atomization > fragmentation. Thus, in Harold’s world, the human family created in the image of the Triune God parses out into pixels, gathering only on the highly volatile principle of the sovereign will of everybody’s one-person world: nuclear fission in the nuclear family, the death of God and so of us.

SIGH.

Ok that was good and so true of the human race…thank God for Jesus because I remember my wandering days, looking for anything but God, only to realize He was what I was actually looking for.