Reframing Immigration—A 'Problem' for God's Mission

Part 1/5: We See What We Speak

Series Introduction

This post is the first in a five-part essay on the “problem” of immigration. In truth, it is less about immigration itself and more about the problem of Christian mission in America. The present immigration crisis has brought this deeper problem to light—one that was otherwise easier to ignore. But the church cannot afford to ignore either.

I am writing as a pastor, not a polemicist, to offer a framework and standpoint—a circumference and a center—that situates us soberly before God prior to all the particularities of this debate in its current maelstrom. It is not an argument for open borders or closed borders—I believe there are reasonable positions on border control across the spectrum. Rather, it is a plea for Christians to align our speech with God’s when we say anything about the nations or our nation in God’s name, as Christ’s witnesses, so that we might more clearly see as God sees.

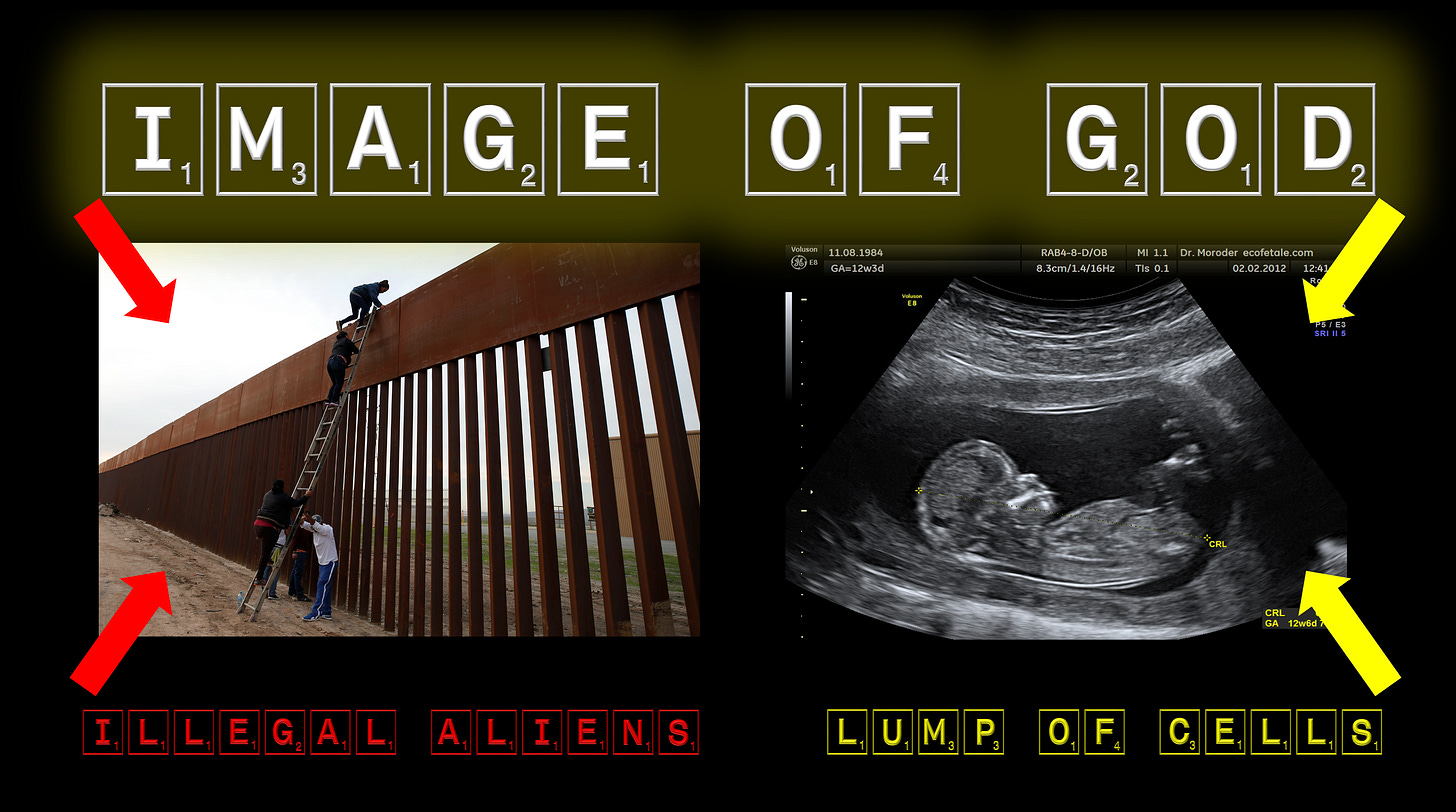

The deepest disagreements among Christians on immigration are not primarily about policy. They are about perception. At the very least, I think through these essays I will be able to help readers understand how language shapes perception in profoundly consequential and readily demonstrable ways (see image below). In so doing, I hope to help restore the church’s faith in the Word of God to transform the world—and our vision to want to see Jesus himself change it.

For those who plan to follow along, over the next five essays I want to slow the conversation down—not to avoid the hard questions, but to ask better ones. My hope is to dig beneath the noise and pressure-test the foundations of our faith, so that whatever we build back up is able to bear the real weight of our confession—Jesus is Lord:

How does language shape vision?

How does rhetoric—scientific, legal, political, theological—shape our frame of reference and how do ‘frames’ limit and order our understanding, for good or for ill?

How are Christians commanded to relate to the nations (within our borders and without) and to governing authorities—and how do these commands inform one another?

What commands should be prioritized in God’s Word as we navigate the complexities of illegal immigration?

How might the New Testament’s way of addressing slavery in the Roman Empire offer wisdom for addressing immigration in the United States?

These five articles—originally written as one (TL;DR!)—build on one another and are best read in sequence, but I have written each so they can be read as one-offs. Titles and topics are as follows:

We See What We Speak—Why immigration is first a theological problem, and the tragic fallout of false confessions

When Frames Become Idols—How the reductive frames of modern myths blind us to the image of God and make us hard of hearing

Law: Romans 13 Is Not God’s Missiology (or Ecclesiology)—How the laws of the land can become a temptation to a powerful church

Gospel: The Great Frame of God’s Commission—All Authority, all nations, and what it means to say Jesus is Lord

Slaves, Obey Your Master—and masters, Free your Slaves—How Paul changed the world through the power of the

SwordWord: A Case Study in Colossae

Throughout the series, a few Case Studies will be included. They are offered to help illustrate the concrete implications of the discussion, but they are not required to follow the logical progression of the argument.

Case Studies will be provided in block quotes like this.

Part 1/5: We See What We Speak

Seeing the World God Speaks

Christianity is a vocabulary. It’s more than that but not less. Language shapes vision. We see what we speak.

Christianity is a story. It’s more than that but not less. Story shapes vision. We see what we seek.

The mission of God advances wherever the world’s vocabulary and story have been transformed by God’s Word. Wherever God’s Word has been transformed by the world’s vocabulary and story, the mission of God is hindered or halts.

The problem being overlooked by Christians in America in all the current controversies over immigration is not about whether Christians should care about law and order, boundaries and borders, criminal justice or social justice, but about which story and whose vocabulary is determining the church’s vision of and mission to the world. It’s about God’s mission according to God’s Word—and about the church taking up its responsibility to the people Jesus died to save and the nations he commanded us to disciple.1

Framing the World: We See What We Speak

Awhile back I used the image above in a sermon. I got some negative feedback from completely different ‘sides’ of the political aisle (which is always welcome—I’m grateful for people who will lean into dialogue when they disagree and not walk away resentfully airing their grievances elsewhere). I think I wasn’t clear enough about what I was not saying, because in both cases it was assumed I was endorsing policies of the opposing side. The image on the slide was intended to preempt that.

I wasn’t talking about policies. I was talking about language—about the words used to describe the world that shape our vision of it. I wasn’t trying to reject or ratify a government policy in God’s name. I was trying to reframe the world according to God’s Word, in this case, to restore a vision of personhood we become blind to the moment we embrace the vocabulary and story of this world.

Words Determine the Frame, Frames Define the World

In the 1980s, Nobel Prize winner and cognitive scientist Daniel Kahneman published a study that shed light on the importance of what he called “framing” for understanding how humans think and reason. Specifically, the study showed how the mind organizes ideas in groupings within various “frames.” Take the following words, for example: scalpel, stethoscope, heart monitor, and bed. Each of these words comes into your mind without context, so your mind creates the context—the frame—in which they belong. The frame, in this case, is a hospital.

But words don’t just create the frame. Consider the way the frame, in turn, situates and gives meaning to the words. In the list above, three of the four words / concepts generally only make sense in the context of a hospital, but the last word fits most naturally in a different context. If I had only listed the word “bed,” or had even just begun the list with it, you would not have begun with the same picture of a bed in your mind as the one you (almost certainly) imagined. You would have imagined the bed most familiar to your experience of a bed, the one you sleep in every night, and that would have evoked an entirely different, and more hospitable, frame: home.

So words evoke a frame that in turn situates and gives meaning to the words. Scalpels belong in a hospital room, not in a toothbrush holder, so if I’ve been thinking about scalpels and stethoscopes all day, my thoughts have to be reframed at home before I can find in my mind the proper (or preferable) place to lay my head.

The point here is this: we don’t simply have a vocabulary. We have vocabularies, and the definitions and meanings of our vocabularies depend largely on a frame of reference and how it situates words in a network of meaning. If I’ve been thinking about ICE protests and trade deficits all day (or all year), my thoughts need to be reframed before “the nations,” as God speaks of them in his Word, can find their place in my head. Herein lies the rub. The problem is, we can get stuck in a frame and end up with scalpels in the bathroom, as it were, and nations without a home, as it is.

If it were just a matter of switching gears to situate the right vocab word in its proper frame, the concept of framing wouldn’t be all that important—and I wouldn’t be wasting your time. The reason it is important is because it describes how all of us process information at the most fundamental level, and because frames can become mindsets, dominant (semi-permanent) frames of reference that inform (and relativize) all others. However, once you understand the concept of framing, you can begin to evaluate your own frames of reference and, in this case, examine whether they align with God’s Word—whether your Christian vocabulary is situated in the proper story.

When Christian vocabulary falls out of its proper frame of reference, everything falls out of its proper place in our minds and hearts, our affections and intentions, in our homes and our neighborhoods and the nations—and alas, “the Son of Man has no place to lay his head” (Lk. 9:58). In other words, we become blind to seeing what God says.

Case Study: The Evangelicals Who Beat Their Wives

Without going too much into Part 2 of this essay—When Frames Become Idols—it is worth pointing out the potential confusions and destructiveness of false framing in our world today. Never in human history has God’s Word been so widely and recklessly subjected to the spin-cycle of deceptions as it is in our digital age, taken out of context and tossed to the brothels in the free market exchange of public (and often political) discourse, where words and definitions exchange fluids and names so that the language of God evolves into “the language of Ashdod” (Neh. 13:24).

Thus, “the name of God is profaned among the nations” (cf., Ezek. 36:23; Rom. 2:24). To profane is ‘to make common’ by improper use—taking the Lord’s name ‘in vain’—leading to confused conceptions of God based on human projection, not divine revelation.

Evidence of this type of ‘profanity’ fills the airwaves, but it has plenty of concrete, empirical forms. According to a recent survey by Ligonier Ministries and LifeWay Research, it’s out in the open: “43 percent of evangelicals said Jesus was ‘not God’ and 65 percent seemed to disagree with the doctrine of original sin. [However], On hot-button social issues like abortion and sex outside of heterosexual marriage, however, evangelicals were nearly unanimous that they are sins.”2 We have here a problem of framing.

If this study is even approximately representative, the implication is that Christian vocabulary has been adulterated to such an extent that nearly half of self-identifying evangelicals in this country are not evangelical Christians—they are evangelical conservatives. In our attempt to bring the nation under the lordship of our faith without the Lord of our faith, we have succeeded precisely, and exchanged the glory of the Gospel of Jesus Christ for images of civil religion resembling mortal man (cf. Rom. 1:18ff).3 We have delivered commands without the Commander—Christ has fallen out of the frame and his commands have been reduced to a godless moralism in his name. Indeed, “the enterprise of the no-god is avenged by its success.”4

The trickle-down effects of this godless evangelicalism are ugly, particularly among men. It leads to absurd statistical contradictions that have long plagued the church’s reputation, and therefore our witness of Jesus Christ, because of so many self-identifying “evangelical Christians” who don’t belong to, and are thus not representative of, the body of Christ.

In her illuminating book, The Toxic War on Masculinity (advocating for the return to godly masculinity), conservative author Nancy Pearcey exposes the way studies that fail to differentiate between what she calls “devout” evangelicals (qualified by their attending church at least three times per month) and “nominal” (“in name only”) evangelicals (who do not attend church regularly) misrepresent the character of practicing Christians, leading to a number of misleading statistics that have been used as fodder for charges of Christian hypocrisy. It’s worth quoting at length:

Whereas “evangelical Protestant men who attend church regularly are the least likely of any group in America to commit domestic violence…Nominal Christian family men do fit the negative stereotypes—shockingly so. They spend less time with their children, either in discipline or in shared activities. Their wives report significantly lower levels of happiness. And their marriages are far less stable. Whereas active evangelical men are 35 percent less likely to divorce than secular men, nominals are 20 percent more likely to divorce than secular men. Finally, for the real stunner: Whereas committed churchgoing couples report the lowest rate of violence of any group (2.8 percent), nominals report the highest rate of any group (7.2 percent)…Sociologist Brad Wilcox, one of the nation’s top experts on marriage, summarized his research in Christianity Today, writing, ‘The most violent husbands in America are nominal evangelical Protestants who attend church infrequently or not at all.”5

Hallow the Name of Jesus

It’s easy to underestimate the potential power of our words to shape the world—especially a world where swords and spears have advanced in power to nukes and satellites. But the word is prior to all, because our words shape the vision of those who give the orders and command the fleets.

We must never forget, moreover, that without the vocabulary and story of God’s Word, the very concepts of freedom and equality by which the Framers declared our nation into existence would not have even been conceivable. The farther our nation drifts from that vocabulary and that story, the more urgent is the calling of the church to be set apart in the distinctiveness of our speech—not for the sake of the nation, but for the sake of Christ, for the sake of his name among the nations—this nation, to which the church has been sent, because we too are included in “all the nations” of the Great Commission.

The more the language of God’s Word gets assimilated within lesser frames of civil religion—commands without a Commander, Christianity without a Christ—the less our confession will carry any inherent weight. Jesus will continue to be reduced to poster boy of partisan political endorsements, torn in two and offered up by “Christians” who are more concerned to build up support for their body politic than to build up the body of Christ. A house divided against itself will all claim Jesus is Lord—and the Son of Man will have no place to lay his head.

This is why, prior to any policy debate, we need to address how we speak, to evaluate how we see. If Christians want the world to see as God sees, they must align their words with God’s Word, align their speech with the way Jesus speaks about everything and everyone—and not just the unborn, not just the immigrant—even, maybe especially, their political opponents. Only God’s Word can reveal God’s vision of the world. But many Christians have given up on the power of God’s Word, because they think the potential power it has can only be realized when it is coopted to influence public policy. That is not the power of God’s Word—it is a blasphemous attempt to baptize the power of the sword.

To see the problem I’m identifying here requires being a Christian: “If you confess with your mouth that Jesus is Lord and believe in your heart God raised him from the dead, you will be saved” (Rom. 10:9). That’s it. Being a Christian, therefore, requires believing (and so imagining) that the fundamental claim of the Gospel is literally true: that Jesus Christ really is Lord—not simply was or will be: is—King of kings and Lord of lords, because all authority in heaven and on earth has been given to him (Mt. 28:18). A Christian is a person who believes in the present reign of Christ and so lives under his lordship in anticipation of his coming judgment. Everyone who does not, is not, regardless of how they “self-identify” or vote (Mt. 7:23). But all are invited, all are welcome, even now, to repent and believe—and begin anew to align their lives and their lips with their confession.

Christianity is a politics. It’s more than that but not less. The substance of our confession depends on it. Out of the abundance of our heart, the mouth speaks. We serve what we seek.

“Seek first his kingdom and his righteousness” (Mt. 6:33).

—King of kings, Lord of lords, Jesus Christ

Footnotes

I will be using the literal (and correct) translation of the Great Commission text in Matthew 28:19 (“disciple the nations”) for the duration of these essays. To understand the problem with the popular mistranslation (“make disciples of all the nations”), see the following essay: Make Disciples—Said Jesus Never.

Civil religion is religious speech and action that “uses” the name of God to advance the interests of the state, not the distinct interests of a given religion. It is based on the assumption that religion in general (and Christianity in particular) exists for the good of our nation—not for Christ himself and so the good of all nations. It is America first, not Kingdom first. It fundamentally flawed at the most fundamental level, therefore, and should probably be regarded as idolatry.

Karl Barth, Epistle to the Romans, p. 44.

Nancy Pearcy, The Toxic War on Masculinity, pp. 36-37.

Powerful start to the series. The framing concept using Kahneman's work is brillant here, esp the way you apply it to how Christians absorb political vocabulary without realizing it shifts their theological commitments. The statistic about nominal vs devout evangelicals is staggering and makes the whole "we see what we speak" fraimwork feel urgent, not just academic.

This topic is vey interesting and absolutely timely. I wrote about it myself recently as well would love to discuss https://theblackwellreview.substack.com/p/love-thy-invader