When Frames Become Idols

Part 2: Reframing Immigration—A 'Problem' for God's Mission

Part 2: When Frames Become Idols—How the reductive frames of modern myths blind us to the image of God and make us hard of hearing.

Note: this post can be read as a standalone but it is best read as part 2 in this series: “Reframing Immigration—A ‘Problem’ for God’s Mission.”

In Part 1 of this series, “We See What We Speak,” I described Christianity as both a vocabulary and a story—it’s more than both, but not less. I pointed out that Christian vocabulary must be understood within the Christian story, or it will be misunderstood.

Vocabularies: Herein lies the significance of framing I discussed in Part 1. We don’t have a vocabulary—we have vocabularies. The meanings of words depend on their frame of reference, because a frame is a network of meaning. [A bed in a hospital frame is different than the one at home. These frames don’t just represent two different kinds of beds but two different networks of meanings, which is why you would invariably rather sleep in one than the other.]

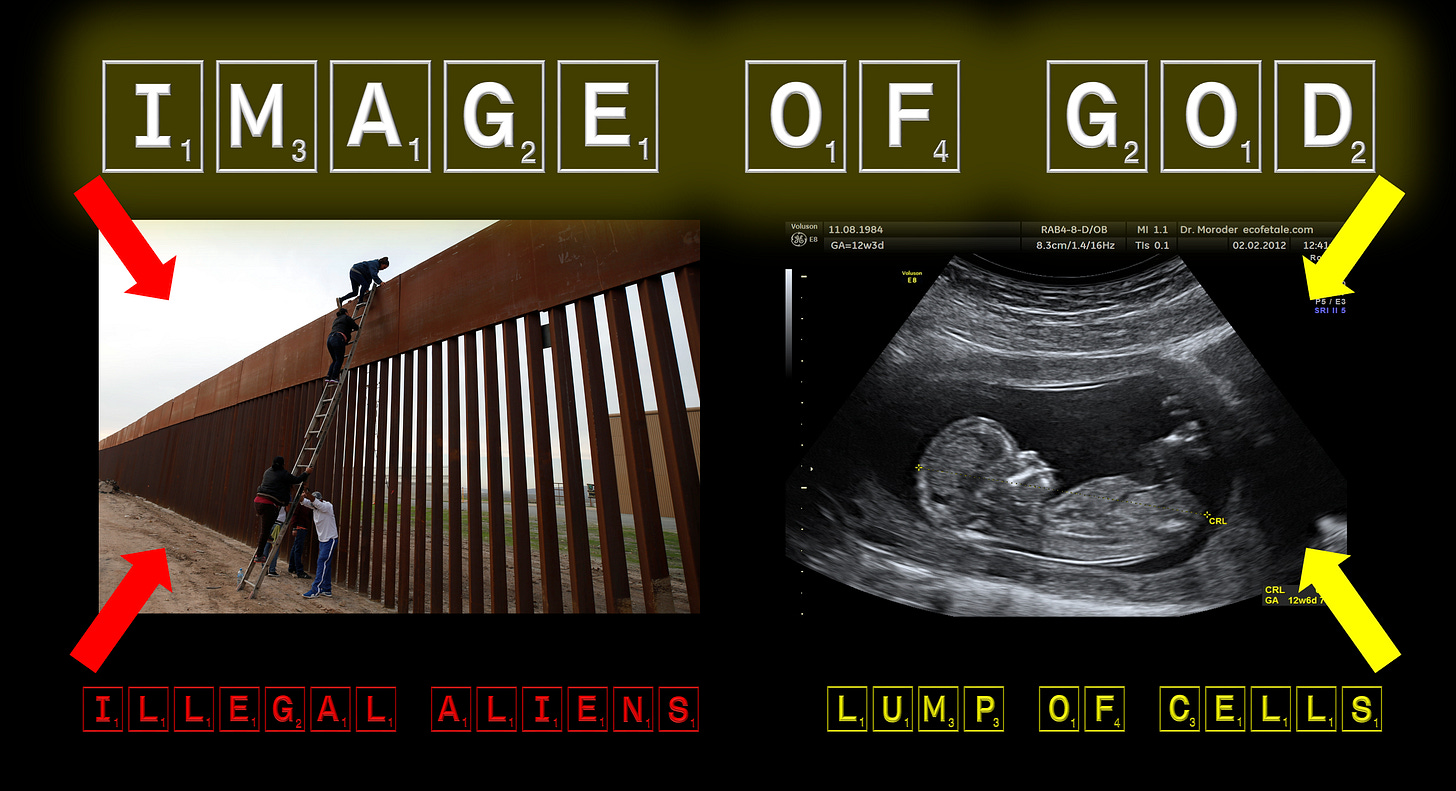

Stories: In this part of the series, I will show how our dominant frames of reference depend on the story that we see ourselves inhabiting. When we inhabit a story, that story has become our mythology. What you see in the images below (from Part 1) depends largely on your mythology. Yes—we all have mythologies.

We all see the world through mythological lenses. Walk with me here, and you will see what I mean. First, we’ll begin with stories for proof of concept.

Right Savior + Wrong Story ≠ Salvation

Stories function as elaborate frames with distinct networks of narrative meaning, distinct vocabularies. A lion in the news means something different than a lion in Narnia than a lion in the Wizard of Oz. The same word has a different network of meaning in a different narrative frame. Jesus is attested to and revered in both the Bible and the Quran, but they tell two different stories about who Jesus is. Same name, different story—different narrative frame.

Even the same phrase can mean something entirely different in different narrative frames. Mormons, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and Christians all confess “Jesus is Lord,” but each means something different depending on the story within which the confession is framed. Same phrase, same confession, different story, different narrative frame. The Bible warns about precisely this.

The Apostle Paul once wrote, “if you confess with your mouth that Jesus is Lord…you will be saved;” Peter, at Pentecost, proclaims, “everyone who calls on the name of the Lord will be saved” (Rom. 10:9-10, 13; Acts 2:21). Jesus said, “Not everyone who calls me ‘Lord, Lord,’” will be saved (“will enter the kingdom of heaven,” Mt. 7:21-23). Why? Because it’s possible to have the right Name, wrong narrative, right King, wrong kingdom, right Savior, wrong story.

The truth of our confession—Jesus is Lord—depends on the right narrative frame.

Case Study: Peter himself found this out the hard way. He was first to confess Jesus as “the Christ” (Mt. 16:16; Mk. 8:29) but then denied the story about “the Christ” that was soon to unfold, which Jesus immediately after revealed: “From that time Jesus began to show them that the Son of Man must suffer many things and be rejected…and killed, and after three days rise again” (Mt. 16:21; Mk. 8:31). Peter embraced the Savior but rejected the story. “Peter took him aside and began to rebuke him…” Jesus, in turn, rejected Peter, and called his very salvation in question: “Get behind me, Satan!” (Mt. 16:23; Mk. 8:33). Right Name, wrong narrative. Right King, wrong kingdom. Right Savior, wrong story.

It would be, at the very least, imprudent not to consider the possibility that we could make the same kind of mistake today, 2,000+ years later, in a world with ever more competing stories. One of the challenges in evaluating our “story,” however, is that we don’t typically imagine ourselves existing within a particular story, a particular narrative frame, largely because we imagine ourselves existing in an “objective” story called “history.”

Modern Mythologies: On the Making of Frames

Without getting into the weeds here, suffice it just to say while history is itself objective, no human being understands it objectively—none of us see the whole, none of us are God!—and all of us imagine ourselves and interpret our world not on the basis of history but on the basis of a story—our mythologies. For Christians, the goal is that we would imagine ourselves and interpret our world on the basis of the Christian story.

To say Christianity is a story, and not just a history, I need to describe its mythological function, without getting stoned as a heretic (or hippie). I will qualify it from the outset with the words of C.S. Lewis:

Now the story of Christ is simply a true myth: a myth working on us in the same way as the others, but with this tremendous difference that it really happened.1

Mythologies aren’t merely make-believe stories but are embedded in language. When we speak of “myths” as stories primitive people believed about the primordial past, we neither understand their myths nor ours. Consider Mary Midgley’s description of myth in her illuminating (though not without controversy) book, Myths We Live By:

Myths are not lies. Nor are they detached stories. They are imaginative patterns, networks of powerful symbols that suggest particular ways of interpreting the world. They shape its meaning. For instance, machine imagery, which began to pervade our thought in the seventeenth century, is still potent today. We still often tend to see ourselves, and the living things around us, as pieces of clockwork: items of a kind that we ourselves could make, and might decide to remake if it suits us better. Hence the confident language of ‘genetic engineering’ and ‘the building-blocks of life’.2

God’s Word is intended to provide for us the imaginative patterns and networks of meaning that give us a basis for interpreting the world. To the degree some other mythology is determining these imaginative patterns and symbolic networks of meaning, we become blind to seeing according to the “true myth.”

God’s Word speaks of itself in this way, as a mirror for the present (Ja. 1:23), not merely a window into the past..3 It is that window into the past which reflects back as a mirror for the present, situating us and the world in the reality of the God “in whom we live and move and have our being” (Acts 17:28).

Absolutizing Immanent Frames: The Scientific Frame

Our vision of the world is blinded by the modern mythologies embedded in our language. These blind spots can be detected wherever we find ourselves unable (or exempt) from seeing people as God says he sees them. If a person can be reduced to the vocabulary and story of modern science—a lump of cells—the image of God becomes invisible and “it” becomes disposable. The problem, in this case, is that scientific knowledge has been absolutized and become the frame of all knowledge and so the basis of perception. Consider, again, Midgley’s words:

The reductive, atomistic picture of explanation, which suggests that the right way to understand complex wholes is always to break them down into their smallest parts, leads us to think that truth is always revealed at the end of that other seventeenth-century invention, the microscope. Where microscopes dominate our imagination, we feel that the large wholes we deal with in everyday experience are mere appearances. Only the particles revealed at the bottom of the microscope are real. Thus, to an extent unknown in earlier times, our dominant technology shapes our symbolism and thereby our metaphysics, our view about what is real. The heathen in his blindness bows down to wood and stone – steel and glass, plastic and rubber and silicon – of his own devising and sees them as the final truth.4

Whenever frames become ultimate, as absolutes, they become idols. [This is the fundamental thesis of Owen Barfield’s Saving the Appearances: A Study in Idolatry, one of the most insightful and underappreciated books of the twentieth century.]5

To the degree scientific knowledge becomes the frame of perception, rather than content within the frame of God’s Word, we become blind in its reductions to seeing what God says he sees: the God who says he knits us together in our mothers’ wombs, the God who himself became a lump of cells in Jesus—Incarnation in utero.

Reframing accordingly does not require a denial of scientific knowledge but of its reductions and restrictions. Even after we’re born, we’re all lumps of cells, but we cannot be reduced only to lumps of cells if God’s Word establishes the frame, because at the foundation of all cells is the face of the living God “in whom we live and move and have our being” (Acts 17:28), our Creator. God’s Word expands our vision precisely in its reductions to the transcendent essence of things and people.

We’re not merely lumps of cells, therefore—we’re whole creatures, made in the image of our Maker (Gen. 1:26-28). The world is not governed by natural laws—it’s governed by the Law-Giver, Jesus Christ, who “upholds all things by the Word of his power” (Heb. 1:3). There’s no such thing as “nature,” of some thing that naturally exists apart from God that frames reality independent of God. The frame is creation, not nature, and therefore “the heavens declare the glory of God” (Ps. 19:1).

How scientific knowledge and the revelation of God’s Word are related can and should be an ongoing discussion, but science must always be understood within the frame of creation according to God’s Word. So too politics.

Absolutizing Immanent Frames: The Political Frame

The way our political leaders (and sadly many ideologically captured Christian leaders on the right and on the left) speak about people, much less “illegals,” blinds us from seeing what God says he sees in them. Political rhetoric is highly reductive, leading to a commensurately restrictive vision when it becomes absolute—the frame—limiting people to an America-centric myth and mode of thinking that is increasingly hostile and inhumane.

God’s Word gives us a vocabulary and a story that defines the world, determines value and meaning, and describes how things are—or ought to be—related (as described above). I know I have a different relationship and set of responsibilities to the image of God than a ‘thing’ that reduces to a lump of cells, but what about a person who is reduced to an illegal alien. Are they disposable as well—or just deportable?

Where do our reductions take us? Is legal status our final reduction? Does law replace spirit? Does citizenship trump the imago Dei? Does our president’s “America first” policy shape our vision of the nations more than our Lord’s “seek first” command? Do our founding documents and legal fictions shape our vision more than the God in whose name they were written? What is the standard that relativizes the measures? In what—in whose—frame does the church in America exist? Is God’s Kingdom framed within our national borders—and are the nations framed out?

I don’t think they have to be. As I said in Part 1, I’m not calling for open borders from our governing authorities. My concern is not to influence politics but how political rhetoric is influencing the church. There was a time when this was not such an urgent matter, when, in fact, Christian rhetoric seemed to frame and limit what our politicians could get away with saying and the policies they proposed.

Take three minutes and watch the clip below from the 1980 presidential debate between Republican candidates George H.W. Bush and Ronald Reagan, concerning education for children of illegal immigrants:

Consider just how dramatically and perversely our political rhetoric, and so our framing, has evolved. The power of politicians’ (especially a president’s) speech cannot be underestimated, because, first of all, like the soldier who recognized the authority of Jesus’ words, as the Commander in Chief the president can say: “I have soldiers under me. And I say to one, ‘Go,’ and he goes, and to another, ‘Come,’ and he comes,” (Mt. 8:9)—and to another, ‘Bomb,’ and he bombs.

Second, a leader’s rhetoric normalizes speech for those who follow. It configures reality, shaping what they love and hate, treasure and despise, praise and protect, hope and fear, how they orient themselves to people, or against people. Presidents are myth-makers, worldview shapers, providing the imaginative patterns and networks of meaning by which citizens situate themselves and define their relationships on the world stage.

Furthermore, political leaders orient people toward the future, the future in which Jesus is coming back, with exactly the kind of rhetoric that leads people to believe Jesus is not coming back. As it’s been said, politics is man’s attempt at mastery over the future. Our politicians all seem to be in the habit of attempting to frame people out of the future of their vision of our nation.

When Christians repeat and retweet their words, we are liable to cast shadows on the world in which we’ve been sent to shed and spread “the light of the gospel of the glory of Christ, who is the image of God” (2 Cor. 4:4). Echo chambers are loud and windowless. The stories we tell ourselves in this country and the vocabulary of our vernacular are increasingly expanding our blind spots into an eclipse.

And uttering Christian speech into the echo chamber does not automatically add light to the darkness—it often just renames darkness as light. Christian vocabulary all too often is coopted for use within a political frame for ends that can sound very “Christian” but are decidedly not. Words like “righteousness” and “justice” and “Jesus” and “Lord”—and even confessional truisms like “Jesus is Lord,” as shown above—can become lies if they are uttered or understood within the wrong frame. Jesus warned about precisely this kind of deception among those who associate his name with worldly power (Mt. 7:21-23), rejecting the meekness and weakness characteristic of his kingdom (Mt. 5:2-12).

The vocabulary and story that frames the church’s relationship to immigrants, illegal and otherwise, is not based merely on a description but a prescription—a command— in which all reality is ultimately framed—and it is not the commands either of the Mosaic Law or the ‘laws of the land’ alluded to from Romans 13. It is the command of the Great Commission, which frames the world in ultimate reality and defines the church’s relationship and responsibility to all nations, all peoples, all ethnos, according to the Gospel of God’s Word.

Before moving on to examining precisely how the Great Commission frames the world (Part 4 of this series: “The Great Frame of God’s Commission”), and why we should privilege the Great Commission text (Matt. 28:16-20) above all others in consideration of this question, it will be necessary to preempt some of the arguments that regularly privilege the text from Romans 13 above all others regarding the church’s relation to governing authorities and the laws of the land. This will constitute Part 3 of this series: “Law: Romans 13 Is Not God’s Missiology (or Ecclesiology).”

Until then—continue to see the world God speaks, and speak the world God sees!

Footnotes

Lewis, C. S. The Collected Letters of C.S. Lewis, Volume 1: Family Letters, 1905-1931 (p. 977).

Midgley, Mary. The Myths We Live By (p. 1). Case Study: For an absurd example of how this mythology has begun to manifest in the hubris of bioengineering in recent years, I’ll just refer you to one Brian Johnson, “The Man Who Thinks He Can Live Forever.”

According to the great Homer scholar Milman Parry, The Making of Homeric Verse: The Collected Papers of Milman Parry, “The ancients,” uninhibited as they were from the illusions of modern epistemology, “by their literature turn the past into the present, making it the mirror for themselves, and as a result the past as it is expressed in their literature has a hold upon them which shows up in the flimsiness of the hold which our past literature has upon ourselves” (p. 409).

Midgley, Ibid.

Cf., Barfield, Owen. Saving the Appearances: A Study in Idolatry. Barfield suggests that the absolutizing of scientific knowledge was the essential shift that took place in the Copernican Revolution, not simply a shift from a geocentric to a heliocentric model of our solar system, but a shift to thinking of the model itself as an ultimate, self-referential truth—in Plato’s sense of the term (truth), otherwise reserved only for transcendent truths. Barfield writes of scientific knowledge (knowledge that comes through observation / experimentation): “Since all we perceive is continually changing, coming into being and passing away, this kind of knowledge grasps nothing permanent and nothing therefore which can properly be called ‘truth.’…The real turning point in the history of astronomy and of science in general…took place when Copernicus…began to think, and others…began to affirm that the heliocentric hypothesis…was physically true” (pp. 46-50). To regard something as “physically true” is, for Barfield and other rational minds, an oxymoron, like saying something (other than the Incarnate Word) is “immanently transcendent.” Thus, “it was not simply a new theory of the nature of the celestial movements that [the Church] feared, but a new theory of the nature of theory; namely, that, if a hypothesis saves all the appearances, it is identical with the truth” (p. 50-51).

Powerful argument about the absolutizing of political frames. The Barfield reference on idolatry nails the core issue: when a specific mode of knowing (whether scientific, political, legal) becomes the frame instead of content within the biblical frame, we lose sight of imago Dei. That 1980 debate clip is jarring compared to current rhetoric. I've seen churches where legal status functionally determines human worth more than the image-bearing argument does. The reall test is whether biblical language is being deployed within political frames or political issues addressed wthin biblical frames.